By Mark Johanson 26th August 2020

Amid Covid-19, new programmes are popping up that invite workers to settle abroad and work remotely. Could we all soon become ‘digital nomads’?I

In early March, Manhattan resident Sadie Millard was visiting her boyfriend in Bermuda as New York City began shutting down due to Covid-19. Rather than return home, she logged on from her boyfriend’s place to remotely do her job as the chief administrative officer of a broker-dealer on Wall Street.

Now, Millard is hoping she doesn’t have to return to New York City – at least for a while. She’s applying for a new one-year residential certificate via the Work from Bermuda programme, which went into effect on 1 August. It would allow her to legally live and work remotely for up to 12 months in the British Overseas Territory, which lies in the North Atlantic about 1,050km (650 miles) off the US’s North Carolina coast.

“My thought was, if I’m going to be here or there, I’d rather be in Bermuda where I feel much safer given the strong rules and regulations the government has set up for testing and managing the virus,” she explains. “And if I have to get back to New York for any meetings, it’s almost quicker to fly in from Bermuda than to drive in from [New York vacation spot] The Hamptons.”

Bermuda is among a handful of small territories and nations around the globe which, after successfully managing the first wave of the virus, are now launching year-long remote worker visas in hopes of cushioning battered economies with an influx of monied foreigners. These new visa schemes posit a version 2.0 of the ‘digital nomad’ lifestyle – one that’s slower, more calculated and, in some cases, aimed at an entirely different audience now that remote work has entered the mainstream.

With Bermuda’s Work from Bermuda programme, remote workers can get a one-year residential certificate to work – and play – on the island (Credit: Alamy)

A mid-pandemic shift

The corporate world, which has been traditionally resistant to remote work, has become much more willing to offer the option as a result of the pandemic. In a global poll by research and advisory firm Gartner, more than 80% of 127 company leaders surveyed said they plan to allow remote work at least part time even after it becomes safe to return to the office. It’s good news to the many workers who’ve spent lockdown envisioning ways of working that don’t involve sharing space with their spouse at the kitchen table.

“People have spent the past four decades asking for more flexibility to work from home, and the pandemic has done for that remote-work conversation what decades of union bargaining has never been able to achieve,” says Dave Cook, a PhD researcher at University College London’s Department of Anthropology, who specialises in digital nomadism.

These new visa schemes posit a version 2.0 of the ‘digital nomad’ lifestyle – one that’s slower, more calculated an aimed at an entirely different audience

It’s why options such as working from Bermuda are not only appealing – but potentially realistic, too.

Government officials in Bermuda, which reopened its borders on 1 July, noticed that tourists were asking how to extend their 90-day entry visas. Meanwhile, the tourism community saw visitors doing things they’d never done before, such as joining gyms and booking villas for months on end.

“That was the lightbulb moment for us,” says Glenn Jones, interim CEO of the Bermuda Tourism Authority. Most of the territory’s 131 remote-worker applicants so far are not the entrepreneurial millennials who have flocked to low-cost digital nomad hubs like Bali, Medellín and Lisbon over the last decade. Rather, they’re much like Millard: well-heeled businesspeople from major East Coast hubs in North America who have been weekending on Bermuda for years.

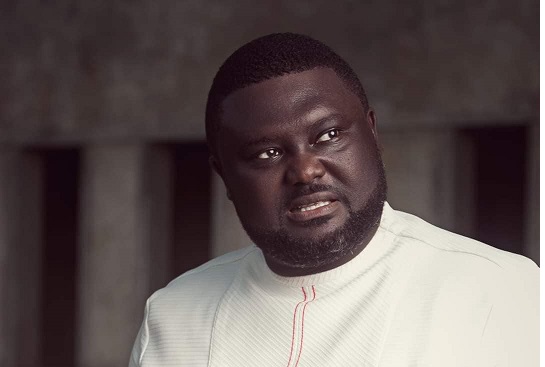

Manhattan resident Sadie Millard is among the workers applying for a visa to stay in Bermuda for a year (Credit: Sadie Millard)

Other than the $263 (£199) application fee, Bermuda has relatively few restrictions on the visa, which allows for multiple entries and exits. You do have to provide valid health insurance, demonstrate ‘sufficient’ means (though there is no hard figure) and, in the case of students, show evidence of enrolment in a collegiate programme, but are otherwise left to live life as a temporary resident.

“We hope this visa can be a test-drive for some business people – even if they haven’t necessarily set out on a test drive – as they might fall in love with the place and want to make it a permanent business home,” says Jones.

A unique opportunity

Bermuda is just one example of these emerging remote-work programmes. The Caribbean island of Barbados implemented a similar 12-month Welcome Stamp plan on 24 July. It has a higher fee than Bermuda’s scheme ($2,000 for individuals or $3,000 for families) and bar for entry (applicants must make an annual income of at least $50,000). Another tourism-dependent country, Georgia, announced a similar project to lure digital nomads in July, though Economy Minister Natia Turnava has released few details.

All places offering these new visas have seen relatively few coronavirus infections, and each has enacted strict protocols

Most of these schemes arose as speedy remedies to buffer the hard-hit tourism sector with long-term travellers who pose fewer Covid-19 risks than in-and-out visitors. Yet, in some countries, this new type of digital-nomad offering has been brewing for a while. For instance, the more comprehensive Digital Nomad Visa from Estonia, where tourism makes up just 8% of the economy, is a project two years in the making. Its 1 August launch date just happened to coincide with the pandemic.

“We launched this visa because we saw an opportunity that no country was addressing,” explains Ott Vatter, managing director at e-Residency for the Republic of Estonia. “There was a substantial amount of people who were working illegally on holiday visas, so we thought, why not have the government solve this?”

Estonia commissioned a survey this July within the US market to gauge interest in its Digital Nomad Visa, given the current climate. It showed that 57% of respondents would consider living in another country for remote work, with cheaper cost of living and cultural experiences being the top drivers. That figure was much higher among workers aged 18 to 34 (63%) than those aged 55 and up (38%).

Estonia’s Digital Nomad Visa programme, which went into effect 1 August, was in the works before the coronavirus hit – and now may be even more desirable (Credit: Alamy)

Countries including the Czech Republic, Mexico and Portugal have all introduced visas in recent years that cover freelancers, but Vatter says the new Estonian Digital Nomad Visa is much broader in scope, allowing teleworking from Estonia for a wide array of location-independent workers, including those with full-time foreign employers. Applicants must pay a 100-euro ($120, £90) fee, provide evidence of health insurance and show proof of at least 3,504 euros ($4,180, £3,164) of monthly income during the six months preceding arrival, but there are no eligibility restrictions based on work sector or country of origin.

Vatter says the new visa programme aims to attract at least 1,800 applicants, who can easily socially isolate, if desired, with 60% of the nation covered in forest. Like Jones, he hopes the nomads will be enticed to stay on indefinitely, either by renewing their visas or applying for residency.

“Estonia is a very small country and we don’t have many natural resources to have a major voice in a global economy,” he explains. “What we are good at is being quite efficient and technologically driven, so we think that is an advantage for us and we use that to compete and attract the best talent.”

What this term ‘digital nomad’ will mean in a year’s time from now is a big question – Dave Cook

All places offering these new visas have seen relatively few coronavirus infections, and each has enacted strict protocols – ranging from mandatory 14-day quarantines upon entry to regimented Covid-19 testing before and after arrival – in order to avoid potential outbreaks or local resentment. Yet, with a lack of economic impact studies conducted in advance, it remains to be seen just what effect – if any – these visas may have on the nations and territories promoting them.

A new type of remote-work culture

What’s clearer to discern is that the number of people able to apply for these kinds of visas may be growing – at least, among those whose jobs have been less affected by the global economic downturn.

Marilyn Devonish, a flexible-work strategist based in London, says there’s been “a seismic shift in the way the world works, with remote and flexible working likely to become the norm after the pandemic is over once organisations learn how to effectively manage and motivate remote employees”.

Beginning 24 July, Barbados implemented a Welcome Stamp plan to allow visitors to work from the Caribbean island for 12 months (Credit: Alamy)

And if these employees can log-on from abroad, she thinks her native Barbados could become a model for others to follow. “The dream used to be to work somewhere like Thailand, but I foresee Barbados and other islands that fit the bill becoming the Caribbean versions once correct standards and procedures are in place.”

Cook, the anthropologist, isn’t so sure. They remain sceptical about some of the hastily formed remote worker visas, saying the idea of digital nomadism – with all its idealistic images of laptops on beaches – is often used as a lazy marketing tool. Some countries, they say, are “just looking for ways to increase visitor count without really understanding the digital-nomad perspective, or that these people like to go places where there are coworking spaces, networking events and a sort of structure that doesn’t necessarily arise overnight.”

But they do think that these new visas suggest “we are going to get a merging of this digital-nomad subculture and this global conversation about remote work”.

The emergence of these programmes may mean that an entirely new segment of the workforce that never before considered working from abroad will now realise its potential allure. And, for digital nomads who are already looking abroad, the set-up of these semi-permanent schemes are encouraging them to slow down, settle in one place for a while and use the opportunity as a ‘test drive’.

“What this term ‘digital nomad’ will mean in a year’s time from now is a big question,” says Cook. “But people are beginning to dream again, and they’re imagining a new and better future.”

Source: BBC.com